How Heavy Is “Heavy Enough” to Improve Bone Density After 50?

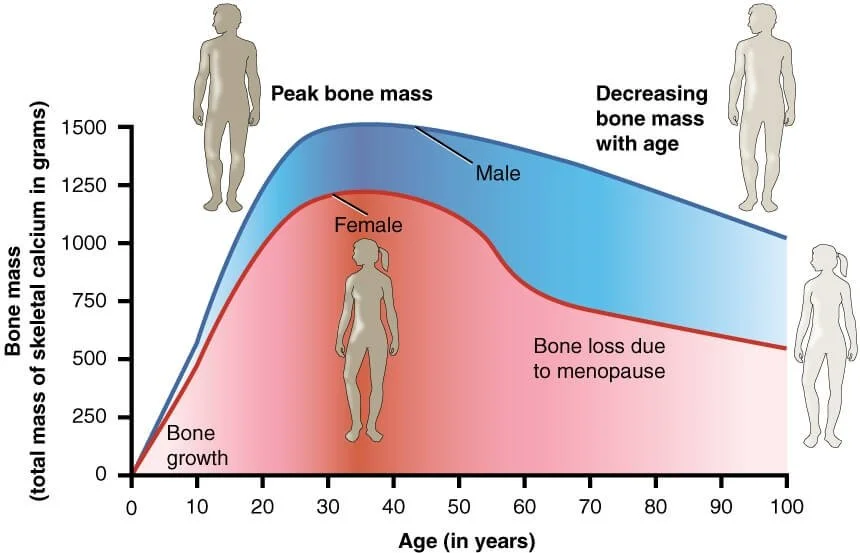

After age 50, declines in bone mineral density are common and often accelerate with inactivity, hormonal changes, and reduced exposure to impact or heavy loading. This increases fracture risk and the likelihood of osteopenia or osteoporosis. Resistance training is widely recommended for bone health, but not all exercise produces the same effect. Bone responds to mechanical strain, not just effort or movement.

To stimulate bone adaptation, loading must exceed what’s known as a minimum strain threshold. If the strain placed on the bone is too small — even if the workout feels hard — the skeleton has little reason to adapt.

The Minimum Strain Threshold: How Bone Knows When to Adapt

Bone tissue adapts through mechanotransduction, a process in which it senses mechanical strain and responds by increasing formation and reducing resorption. However, the strain must be sufficiently large and novel. Repetitive, low-intensity loading often fails to exceed the threshold needed to trigger this response.

In older adults, this threshold may be higher than it was earlier in life. Age-related changes in bone quality make skeletal tissue less responsive to mild stress, which helps explain why light weights or gentle exercise alone often fail to improve bone density in midlife and beyond. Research consistently shows that moderate-to-heavy resistance training provides a more reliable stimulus for bone adaptation than very light loads.

Early Movement Matters: Why Childhood Play Shapes Bone Health for Life

Many of the adults and seniors I work with grew up playing high-impact, multidirectional sports like basketball, soccer, or running. Earlier in life, their bones were exposed to jumping, cutting, sprinting, and landing forces from many directions—exactly the type of loading research shows is most effective for building peak bone mass during childhood and adolescence.

What often gets overlooked is how that bone strength was built. Years ago, kids weren’t just training for one sport year-round. They climbed fences, jumped rope, played pickup games, fell down, and moved freely. This unstructured free play creates varied strain patterns in bone, which research suggests is critical for long-term skeletal strength.

Today, many kids specialize in a single sport much earlier, often with less overall movement variety. While structured training has benefits, it may not provide the same multidirectional loading that bones need. It will be interesting—and potentially concerning—to see how this shift affects bone density and fracture risk later in life.

As adults age, those high-impact activities usually fade away, even if they remain active. When someone returns to structured training later in life, their bones may no longer be conditioned for the stresses they once tolerated. That’s why I always consider both past athletic history and current bone health. Improving bone density isn’t about recreating youthful intensity—it’s about applying the right amount of load for where the skeleton is now, using principles backed by research and tailored to the individual.

Why “Hard” Workouts Don’t Always Build Stronger Bones

Many adults gravitate toward high-intensity group classes because they’re motivating, social, and feel productive. Exercise in almost any form is beneficial for overall health, and these classes absolutely have value. Most, however, rely on lighter weights, higher repetitions, and continuous movement.

For example, performing squats with light dumbbells for 20–30 repetitions, cycling through fast-paced circuits, or using resistance bands for long sets challenges the heart and muscles but places relatively low mechanical stress on bone. You feel tired, sweaty, and accomplished—but the skeleton may never experience enough strain to trigger adaptation.

Bone responds differently than muscle or the cardiovascular system. It doesn’t adapt to fatigue or time under tension—it adapts to strain magnitude. Lifting a heavier load for fewer controlled repetitions, such as squats, deadlifts, step-ups, or presses performed at higher intensities, creates larger forces through the hips and spine. These forces are what research shows are more effective for stimulating or maintaining bone mineral density.

In other words, moving faster or doing more repetitions isn’t the same as loading the skeleton meaningfully. A slow, heavy set of five well-performed repetitions may provide a stronger bone stimulus than several minutes of continuous light movement. That doesn’t mean high-intensity classes are “bad”—it simply means they serve a different purpose.

When bone health is the goal, training needs to be structured intentionally, with enough load to exceed the minimum strain threshold while still being safe and appropriate for the individual.

What the Research Says About “Heavy Enough”

Studies in older adults and postmenopausal women show that resistance training programs most likely to improve or maintain bone density typically include moderate-to-heavy loads, often in the range of 70–85% (and sometimes up to 90%) of one-repetition maximum. These programs generally use lower repetition ranges, multi-joint weight-bearing exercises, and consistent training over many months.

Research also shows that older adults can safely tolerate these intensities when training is well-designed and progressed appropriately. Even when changes in bone density are modest on a DEXA scan, improvements in bone turnover markers suggest that the skeleton is adapting beneath the surface.

How I Apply This With My Clients

When I work with adults and seniors, improving bone density is never about jumping straight into heavy weights. The process starts with understanding the individual — their training history, injury history, movement quality, and bone health when available.

We first build a foundation of strength, control, and confidence under load. From there, we gradually introduce lower-repetition, heavier resistance exercises using movements like squats, deadlifts, step-ups, presses, and carries. Loads are challenging but appropriate, rest periods are intentional, and the focus stays on quality rather than fatigue.

I don’t rely on constant high-rep circuits when bone health is the goal. Instead, training emphasizes progressive loading over time so the stimulus consistently exceeds the minimum strain threshold required for bone adaptation. For some clients, we also incorporate carefully selected weight-bearing or low-impact variations to introduce different strain patterns that further support bone health.

Just as importantly, I set expectations early. Bone density does not change quickly. Research suggests that two to three bone remodeling cycles — often six to nine months or longer — may be required to see measurable improvements. Strength gains, improved tolerance to load, and increased confidence are often the first signs that the process is working.

Building Bone Resilience for the Long Haul

Resistance training remains one of the most powerful tools we have to support bone health after 50 — but only when it’s applied with intention. Light weights and high repetitions can support general fitness, but bone requires sufficient load, progressive challenge, and time.

“Heavy enough” doesn’t mean reckless or maximal. It means smart, individualized loading that respects both the science of bone adaptation and the person doing the work. When training history, research-based principles, and long-term consistency come together, the result isn’t just stronger bones — it’s greater confidence, resilience, and independence for years to come.

Interested in Applying This the Right Way?

If you’re an adult or senior who wants to improve bone density safely and intelligently, this is exactly how I work with clients.

I’m Garrett McLaughlin, and I specialize in helping adults and seniors train with purpose — particularly those with osteopenia, osteoporosis, or concerns about long-term bone health. In addition to one-on-one coaching, I also lead a Building Better Bones small group training class for seniors.

This program applies all of the principles discussed here: appropriate loading, progressive resistance, balance and strength training, and the consistency needed to support real bone adaptation. Sessions take place at Pure Movement, where the space and equipment allow us to train safely, deliberately, and effectively in a small-group setting.

If you’re ready to move beyond light weights and generic workouts — and want a smarter, research-guided approach to building bone resilience — Building Better Bones may be a great fit.

If you’d like to learn more or see if the program is right for you, I’d be happy to start with a conversation.