Understanding Spine Loads During Exercise: How to Train Smarter, Stay Stronger, and Protect Your Back

If you’ve ever been told to “avoid squats or deadlifts” because of your back, you’re not alone. Many people with a history of lower back pain or injury feel uncertain about which exercises are safe. But here’s the good news: most movements aren’t inherently dangerous — they simply need to be approached with the right understanding and progression.

This article breaks down what modern research says about how different exercises load the spine, why no movement is automatically “bad,” and how to progressively build strength and resilience so your training can stay both effective and pain-free.

Why Spine Health Matters

Low back pain (LBP) is one of the most common musculoskeletal complaints worldwide, affecting up to 80% of adults at some point. For many, it’s not a single exercise that triggers pain — it’s a combination of fatigue, poor technique, and doing too much too soon.

The spine is designed to move, bend, twist, and carry load. When you train intelligently, exercise can actually make it stronger, not weaker. Understanding how different movements stress the spine helps you make better decisions for your body and goals.

What Does “Spine Load” Really Mean?

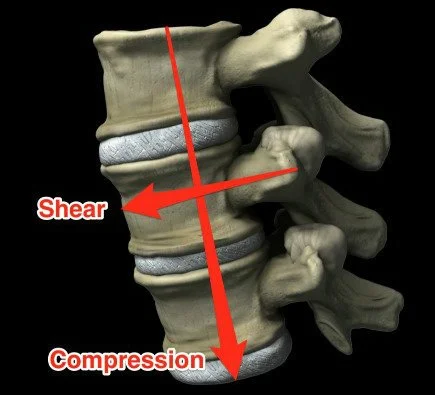

Spinal loading refers to the forces acting on your vertebrae and discs when you lift, carry, or move. These include compressive forces (pushing down along the spine) and shear forces (sliding forces acting parallel to the spine).

Recent studies, such as those by Lerchl (2025) and Murray (2025), show that the way you move — your posture, core activation, and breathing strategy — can drastically influence how those forces are distributed. When you brace your core and build intra-abdominal pressure (that “tight belly” feeling when lifting), you actually help your spine handle more load safely.

So instead of avoiding spinal load, the goal is to teach your body to tolerate it through gradual, controlled exposure.

How Common Exercises Load the Spine

Let’s look at how popular strength exercises differ in the way they load your spine — and what that means for you.

Back Squat: The barbell sits on your upper back, creating a vertical load through your spine. This produces high compressive forces but also strong core activation. It’s great for overall strength, but beginners should focus on posture and control before loading heavily.

Front Squat: Holding the bar in front keeps your torso more upright, reducing spinal compression while still challenging the legs and core. It’s an excellent choice for people returning from back pain or those who want a squat that’s a bit easier on the lumbar region.

Deadlift: Because you hinge forward, the deadlift places both compressive and shear forces on the spine. However, when done with good bracing and neutral alignment, it can safely build tremendous strength in the posterior chain.

Romanian Deadlift (RDL): This variation emphasizes hip movement more than knee bend. It generally involves lower loads but more shear force. The RDL is great for developing hamstring and hip strength while maintaining spine stabilization.

Hip Thrust: The load is applied horizontally across the hips, producing minimal spinal compression. It’s perfect for strengthening glutes with very little stress on the lower back.

Goblet or Belt Squat: By holding weight at chest level or attaching it below the body, these exercises minimize spinal load. They’re ideal for beginners or those rebuilding after injury.

As Varrassi et al. (2025) and Schellenberg et al. (2017) found, adjusting trunk angle, bar position, and exercise type can significantly change spinal loading patterns — which is exactly why variety and intelligent programming matter.

No Exercise Is Inherently Bad

A key message from recent biomechanics and rehabilitation research is this: load is not the enemy. Studies such as De Bruin et al. (2024) show that mechanical load by itself doesn’t cause pain — rather, pain often arises when tissue capacity doesn’t match the demands being placed on it.

That means an exercise like the deadlift isn’t “bad.” It’s simply demanding. The right question isn’t “Should I avoid this movement?” but rather “Am I ready for this movement right now?”

Choosing the right exercise depends on your:

Goals: Are you building strength, recovering from injury, or maintaining fitness?

Injury history: What does your back currently tolerate?

Available equipment and comfort level: What tools are available and what is your training experience?

A person recovering from disc irritation might start with hip thrusts and goblet squats before reintroducing deadlifts. Someone else might begin with RDLs to strengthen the hips before progressing to full squats. The exercise isn’t the problem — it’s the fit between the exercise and the person.

The Power of Progressive Loading

Perhaps the most important concept in spine-friendly training is progressive loading — gradually increasing the demand on your body so that it adapts and becomes stronger.

Research from Trybulski et al. (2025) and Lu et al. (2025) shows that people who build capacity through controlled, incremental resistance training experience less pain and better spinal control over time.

Here’s how to apply this safely:

Start with what you can tolerate now, even if that means light weights or shorter ranges of motion.

Increase load gradually — a general guideline is no more than about 10 percent per week, but listen to your body.

Manage total spinal stress by incorporating different movements. Changing exercises occasionally — for example, rotating between hip thrusts, RDLs, and squats — exposes the spine to varied forces, reducing repetitive strain.

However, consistently progressing one key exercise over time also builds specific tolerance to that movement’s unique demands. In other words, variety helps you stay balanced, while consistency helps you adapt. Both matter.

Pay attention to how you feel. Some muscle soreness or stiffness is normal, but sharp or radiating pain is a signal to modify or rest.

The principle is simple: gradual exposure builds resilience. Your spine gets stronger by being trained — not by being protected from all load.

Building a Resilient Spine

Training for a healthy back is less about “avoiding injury” and more about building robustness. The goal is to move with confidence, strength, and control.

Focus on:

Solid technique and body awareness.

Consistent, sustainable progression — no big jumps in volume or load.

A strong foundation of core stability and hip strength to support the spine.

As rehabilitation expert Mattera (2025) puts it:

“The spine is not fragile; it becomes resilient when we progressively expose it to meaningful load.”

When you approach exercise this way, lifting becomes not something to fear, but a tool for long-term health.

Putting It All Together

Everyone’s journey looks different. A client recovering from back pain might start with body-weight glute bridges and goblet squats. As control and confidence improve, they might progress to front squats, then eventually back squats or deadlifts. Others may prefer to stick with variations like the hip thrust that align with their comfort level and goals.

The key is thoughtful progression — not rushing, not comparing, but building step by step. Your spine, like any other structure in the body, adapts when given the right challenge and time to grow.

Train Smart, Move Confidently, and Build a Stronger Spine

Your spine is designed to handle load — in fact, intelligently applied load is what keeps it strong, stable, and capable. The key isn’t avoiding stress altogether, but managing it wisely through movement, awareness, and gradual progression. Every time you train, you’re giving your body a chance to adapt and grow stronger, not just in your muscles but in the connective tissues, bones, and nervous system that keep you moving safely.

No exercise is inherently bad; it’s all about finding what fits you. The right movement depends on your history, goals, and comfort level. A back squat might be perfect for one person but uncomfortable for another, while a hip thrust or front squat might feel smooth and pain-free. What matters most is matching the exercise to your current capacity — then building from there with consistency and intention.

Progressive loading doesn’t just build strength; it builds confidence. When you gradually challenge your body, you develop trust in your own movement again — especially if you’ve dealt with back pain or injury in the past. That trust is what turns training into a lifelong habit instead of a temporary fix.

A well-rounded program strikes the right balance between variety and consistency. Variety challenges your body in new ways and prevents overuse, while consistency allows your tissues and nervous system to adapt to specific forces over time. Together, these two elements create sustainable progress — helping you stay strong, mobile, and injury-resistant for life.

If you’ve experienced back pain before, or if you simply want to prevent injury and move with confidence, it’s time to take a smart, science-based approach to your training. My programs are built from years of experience in the athletic training/sports medicine field, blending the precision of rehab principles with the effectiveness of performance training. Whether you prefer personalized in-person coaching or a self-guided training plan designed to follow at your own pace, each program is tailored to your goals, movement history, and comfort level.

You don’t need to fear lifting or wonder if you’re doing the right exercises for your back. With the right plan — and the right guidance — you can build a body that’s strong, resilient, and capable for years to come. If you’re ready to train smart, move confidently, and make your workouts safer and more effective, reach out today to learn more about how we can build your personalized program together.

Remember: your spine isn’t fragile — it’s adaptable. With mindful movement and smart progression, it can become one of your greatest strengths.

Research Articles:

Varrassi et al. (2025). Bioengineering. “Biomechanical Evaluation of Spinal Function in Low Back Pain.”

Lerchl, T. (2025). “Individualized Musculoskeletal Models of the Torso for Spinal Biomechanics.”

Trybulski et al. (2025). Scientific Reports. “Impact of Isolated Lumbar Extension Strength Training on Low Back Pain.”

De Bruin et al. (2024). JOSPT. “Insufficient Evidence for Load as the Primary Cause of Low Back Pain.”

Pranata et al. (2024). JOSPT. “Neuromuscular Control and Resistance Training in Chronic Low Back Pain.”

Murray, S. (2025). “Role of Intra-Abdominal Pressure and Lifting Velocity in Spine Stability.”

Mattera, J.A. (2025). “Strength Training and Exercise Prescription for Rehabilitation Professionals.”